Discover more from State of the Territory News

Unraveling the Mysterious Lives of Bananaquits

The territorial bird of the U.S. Virgin Islands is credited for its beauty, but we never mention how smart they are.

Charlotte Amalie𑁋Spring in the northern hemisphere is here. The grass and shrubs around your home grow thicker, taller, and faster as the rainy season nears. A small sugar apple tree in the distance catches your attention. The small shrub-like tree barely has a few dozen leaves.

The sugar apple tree looks like it’s dying, but a bundle of twigs is wrapped around a few of the loneliest branches. It appears to be an unfinished nest, standing just as tall as you. Days pass, and the nest grows bigger and more visible.

Less than two weeks after your discovery. You spot a bananaquit, meticulously weaving twigs and soft clumps of foliage. The design is simple. The nest is fully closed, but there’s a small opening at the bottom. Only a tiny, agile bird could make its way in without making a fool of itself or damaging the nest.

Weeks go by, and you notice the yellow-bellied bird never returns. You peek inside the nest and realize you’ve been duped. The nest is empty and looks like it’s never been used.

Clever Little Birds

Bananaquits, also known as the yellow breast or the sugar bird𑁋not to be confused with the Yellow-breasted Chat𑁋are the territorial bird of the U.S. Virgin Islands. The bananaquit is one of the most widespread songbirds in the Caribbean and belong to the New World Warblers.

Their nests are typically cup-shaped and made of various materials, including twigs, leaves, and spider silk. A mating pair can make multiple nests in a single season. Researchers like Mario Francis, also known as Bird Man, believe they build nests in different locations for different purposes. Francis is a St. Thomaian and a professional bird watcher and the founder and director of the St. Thomas Audubon Society. He also leads the Junior Gardening and Ecology Academy on St. Thomas.

One nest is used to raise their young, some for daytime naps, and some nests serve as decoys to confuse predators.

Spider silk is five times stronger than steel and almost as strong as Kevlar, the toughest man-made polymer. This means bananaquit eggs are typically nestled away in a blanket of bio-material and the structure of the nest is meticulously reinforced with one of the planet’s strongest forms of silk.

Spider silk contains protein and nutrients that boost the diet of many birds. It’s also water-resistant, so chicks are protected through periods of heavy rain. Their nests are almost exclusively found in casha trees and local Catch-and-Keep (Acacia Retusa) shrubs, both thorned plants.

Unfortunately, not much is known about what they do at night when they aren’t asleep.

Diet and Foraging Habitats

Although bananaquits are typically seen drinking nectar from flowers, they primarily consume worms, caterpillars, and insects. Because they are strong fliers, they also spend some days near inland ponds and mangrove forests.

These freshwater ponds and saltwater ponds are incredibly diverse environments. They also have a lot of insects and different types of larvae. Other populations of bananaquits may exhibit different behaviors and foraging niches based on what’s available in their habitat. In less stable habitats where humans continue to develop and clear rainforests, bananaquits may alter some of the materials used in nest building to adapt to environmental changes.

Not all Birds Migrate

When we think about birds, common things that come to mind are nests, eggs, and seasonal migrations. More than 100 bird species that breed in North America migrate to the Caribbean annually.

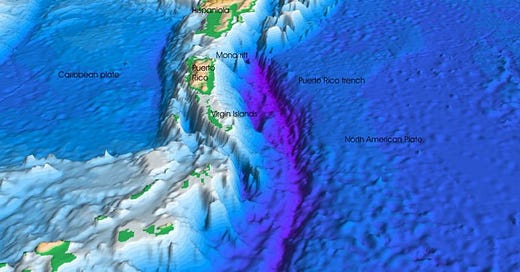

During the autumn and winter months, countless birds end their migration and descend on the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico in search of temperate habitats. Banananaquits in the Caribbean don’t migrate during the winter, but they travel to neighboring cays and islands in search of food during competitive months. The autumn and winter months in the Caribbean tend to be drier as the hurricane season comes to an end and annual droughts set in.

Migration behavior is unique for species native to the Caribbean archipelago. Many native animals, including birds, stay all year round. For example, there are about seven distinct sperm whale clans in the world, including the slightly smaller sperm whales that live off the coast of Dominica. Dominican sperm whales are the only population of sperm whales that choose not to migrate during the winter months. Different species of whales pass through the Caribbean archipelago to give birth and wean their young.

With this in mind, tropical ecosystems in the Caribbean archipelago and the birds inhabiting this region appear far more complex than previously thought.

Subscribe to State of the Territory News

Covering technology and culture in the U.S. Virgin Islands. A new edition of the Watershed Report is published every Tuesday & Thursday night.

You've got an avian treasure trove in Mario Francis. I'll bet he's got some stories to tell. Hint. Hint.